Thomas Jefferson’s Coin Collection

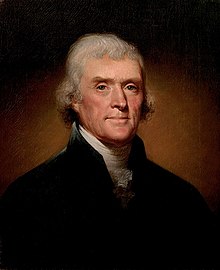

Last updated:Thomas Jefferson is one of America’s most recognized founding fathers – and rightly so.

He was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. He served as our nation’s first secretary of state and our second vice president. And as our third president, he doubled the size of the nation with the Louisiana Purchase.

From a numismatic standpoint, Jefferson also stands out. In addition to the Jefferson Presidential dollar, his image has graced U.S. nickels since 1938. And, of course, he has appeared on both the face and back of $2 Federal Reserve Notes since 1976.

But did you know Thomas Jefferson was also a coin collector? Or that his coin collection helped create the coinage system we use today?

It’s a great story – and all the more so because it’s true. However, to tell it properly, we need to first turn back the pages of history and set the stage…

The American coinage conundrum

A rare 1776 New Hampshire copper

A rare 1776 New Hampshire copperIn colonial America, few people – if any – had coin collections. In fact, money was a troublesome subject for early Americans.

Coins were in short supply in the British colonies, as England didn’t provide enough coins to meet their needs. Despite this, the colonies weren’t permitted to mint their own coinage (although some did).

Making things worse, coins circulating in the colonies often did not stay long. Instead, they made their way back to Europe as payment for supplies.

The colonies did issue their own paper money, but mainly as notes to be redeemed in exchange for coin. What’s more, the quantities were not well regulated. Inflation and hyperinflation eventually rendered them worthless – giving rise to the saying “not worth a Continental.”

Spanish 8 reales, also known as “Pieces of Eight”

Spanish 8 reales, also known as “Pieces of Eight”The first “American” dollar

Without enough coins to go around, American colonists often found themselves forced into bartering or using primitive coinage, such as Indian wampum. Over time, they supplemented hard-to-get British coinage with coins from France, Spain, Portugal, Germany and other nations.

Of these, the Spanish dollar was the most common and trusted. It had a distinctive design. Its purity was consistent, and it was accepted in trade around the globe. Plus, it was easy to use in commerce. To make change, Spanish dollars were cut into eight pieces, or “bits.”

So, while the colonies were British, the Spanish dollar was essentially – at least in trade – America’s unofficial national currency.

After the American Revolution, leaders of the new United States set their sights on fixing the problem. However, things did not go smoothly. The original Articles of Confederation gave both Congress and the states the right to mint coinage.

It quickly became clear that a single national currency system was essential to establishing and maintaining the new nation’s sovereign identity. Something had to be done.

Enter Thomas Jefferson…

Even before the Revolution, Thomas Jefferson knew America needed a better monetary system.

Jefferson loved reading and the pursuit of knowledge. So when his friends travelled to Europe, he often asked them bring him back books. But with British coins hard to come by in any quantity, he was forced to send them with coins from a variety of nations.

And in at least one case, a silver coffee pot!

1797 Great Britain Two-Pence Cartwheel

1797 Great Britain Two-Pence CartwheelIn addition to the problem of having enough coins for commerce, Jefferson was also vexed by the American exchange rates. Each colony maintained its own exchange rates for the many coins that circulated. Factor in the nuances of British coinage, and making change became truly complicated.

The founding father wholeheartedly agreed a new system was needed – and he preferred a simple one. Because, as Jefferson himself noted, “…even Mathematical heads feel the relief of an easier substituted for a more difficult process.”

To Thomas Jefferson, a decimal system made the most sense. He began advocating for the United States to adopt one as early as 1776. And while it took time, his viewpoint prevailed.

In 1784, Jefferson’s “Notes on Coinage” report persuaded Congress, and the United States became one of the first nations to adopt decimal coinage.

Coin collecting with a purpose…

As a true Renaissance man, Jefferson didn’t want the coins of the new United States to just be practical. He wanted them to be on par with those of European nations. So he picked up a new hobby – coin collecting.

Throughout the 1780s and 1790s, Jefferson began assembling a coin collection of copper, silver and bullion coins from many nations, including France, England, Italy, Germany and Holland. But he didn’t collect the coins for himself.

As he explained in a letter to Caspar Wistar:

“While visiting Europe, I thought it might be useful to bring home some specimens of the different coins I met with…I supposed they might furnish subjects for consideration, & sometimes imitation.”

It was a noble effort, and Jefferson’s friends helped him out. In 1786, David Salisbury Franks – who served as secretary to an American mission in Paris – brought back some “Moorish coins” for Jefferson when he returned from Morocco.

Monnaie de Paris (Paris Mint)

Monnaie de Paris (Paris Mint)Around the same time, Jefferson visited the Paris Mint (left). There, he observed the revolutionary minting methods of Jean-Pierre Droz and acquired samples of Droz’s Ecu de Calonne. Jefferson was greatly impressed by the coins.

In fact, some sources claim Jefferson was so impressed he tried to recruit Droz to join the new United States Mint in Philadelphia!

However, it was not to be. Droz ultimately chose England over the U.S. – accepting an offer to join Matthew Boulton’s Birmingham Works instead.

To be continued…

Looking for Part 2 of this article? Click here!

This article was written by Len B.

A lifelong writer and collector, Len is a USAF veteran, New Hampshire native and member of the American Numismatic Association.

Wonderful story Littleton, not only about Thomas Jefferson, but about the history of our US coinage as well. I am anxious to read the continuation.

Thank you Roger! We appreciate you stopping by!

Great article

Thanks Paiul. We appreciate you visiting our blog.