A President, an Inventor and 2 Suffragists Walk into a World’s Fair

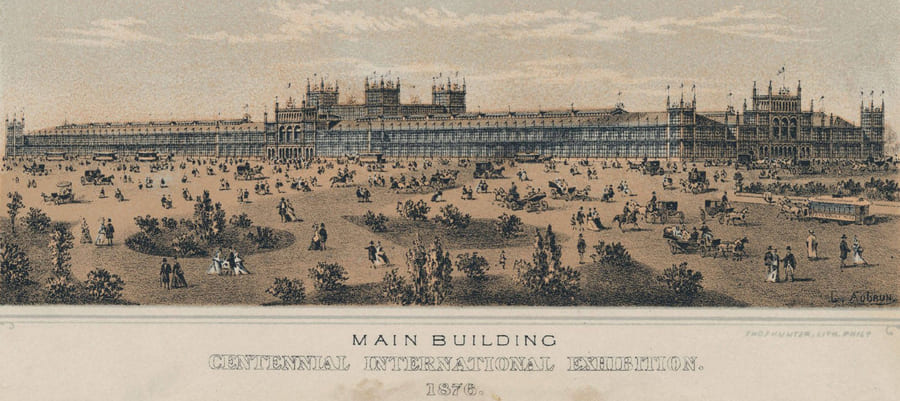

Courtesy of Philadelpia Encyclopedia

Courtesy of Philadelpia EncyclopediaThe morning of May 10, 1876 in Philadelphia dawned with rain. But by 10 a.m., the clouds started to dissolve. The sun began to shine. And the enormous throng of over 185,000 visitors attending the opening ceremonies of the Centennial Exposition was surging past the Fairmount Park gates.

1926 Sesquicentennial of American Independence Commemorative Half Dollar

1926 Sesquicentennial of American Independence Commemorative Half DollarExcept it was no longer just a 100th anniversary celebration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The exposition had bloomed into a full-scale world’s fair hosted for the first time by the United States. Our still-young nation had just 38 states at the time. But 26 – more than half – sent exhibitors, inventors and dignitaries. So did 35 foreign countries.

According to The Perrysburg Journal of Ohio: “The crowd was a little boisterous, perhaps, and a trifle extra-demonstrative as some of the great men ascended the platform. The President was received with cheers, as was proper, seeing that he represented the Nation in the ceremonies.”

Mr. President

Back in 1871, when Civil War hero and Ohio native Ulysses S. Grant was two years into his presidency, Congress passed an act to fete the nation’s 100th birthday. Five years later, all that planning bore fruit and a fancy new name that captured the five-month event’s expanded scope: International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine.

Shortly after an orchestra entertained the crowd with the anthems of foreign nations, Grant stepped up to the podium.

“…fellow citizens, I hope a careful examination of what is about to be exhibited to you will not only inspire you with a profound respect for the skill and taste of our friends from other nations, but also satisfy you with the attainments made by our own people during the past 100 years. I invoke your generous cooperation with the worthy commissioners to secure a brilliant success to this international exhibition, and to make the stay of our foreign visitors—to whom we extend a hearty welcome—both profitable and pleasant to them.”

Grant and his guest, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, then made their way to the 13-acre Machinery Hall, where state-of-the-art technology was on display. Together, the two leaders pulled the levers on the enormous Corliss steam engine that was the hall’s power source, and the exhibit – and by extension, the expo – was up and humming!

Mr. Inventor

Machinery Hall heralded the arrival of the United States as an important industrial power in world markets. A few other inventions beside the Corliss engine stood out, but none more than the modestly sized creation of tinkerer and teacher of the deaf Alexander Graham Bell. In March of 1876, Bell received a U.S. patent for a device that could transmit sound through telegraph wires. He called his invention a telephone.

“My God, it talks!” exclaimed Brazil’s Emperor Dom Pedro, who returned to Machinery Hall in June for the first public activation by Bell of his invention. Bell’s telephone became the most talked-about invention of the entire world’s fair.

Two suffragists

But while new technology, along with such new foods as root beer and popcorn, were experienced inside Fairmount Park, something else was brewing in downtown Philadelphia. Leaders of the National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA) had seized on America’s centennial to renew their call for women’s rights.

NWSA President Elizabeth Cady Stanton requested time on the July Fourth program at Independence Hall to present the 1876 Declaration and Protest of Women of the United States. Among other calls to action, the document demanded the impeachment of U.S. leaders on the grounds they taxed women without representation and denied women the right to a fair trial by a jury of peers.

Instead of a speaking slot, Stanton received six tickets for audience seats. NWSA members convinced her and fellow suffragist Lucretia Mott to proceed with their original intent. When the program began that Tuesday, July 4, 1876, Susan B. Anthony pushed her way to the stage and handed U.S. Senator and President Pro Tempore Thomas W. Ferry, of Michigan, a copy of the Women’s Declaration.

According to one account, “Ferry’s face paled as bowing low, with no word he received the Declaration, which thus became part of the day’s proceedings…”

Anthony then walked outside to join others already gathered there. Just before she started to read aloud the Women’s Declaration, she made this humble plea:

“We ask justice, we ask equality, we ask that all the civil and political rights that belong to citizens of the United States, be guaranteed to us and our daughters forever.”

The course of history would go another 44 years before Congress ratified the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. However, it only was 17 years before the U.S. produced an even bigger fair – the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. But the template for such displays of progress belonged to the Centennial Exposition. By the time Fairmount Park’s gates were closed in November, nine million visitors had had the chance to see new inventions, taste new foods, view new art and listen to newly written music.

2011-S Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Dollar

2011-S Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Dollar 2020 Massachusetts U.S. Innovation Dollar

2020 Massachusetts U.S. Innovation Dollar Prominent Women “Golden” Colorized Presidential Dollar features Lucretia Mott

Prominent Women “Golden” Colorized Presidential Dollar features Lucretia Mott Susan B. Anthony Coin & Stamp Set

Susan B. Anthony Coin & Stamp Set