Vive la Révolution Française!

The summer of 1789 was not going well for Louis XVI, king of France (right). National debt was rising higher than a powdered pompadour. It was year two of a devastating food shortage. Military conflict at France’s borders was ongoing.

The summer of 1789 was not going well for Louis XVI, king of France (right). National debt was rising higher than a powdered pompadour. It was year two of a devastating food shortage. Military conflict at France’s borders was ongoing.

Taxes weren’t producing anywhere near the amount needed to keep the country running. The working class was taxed beyond its ability to pay. The nobility refused to pay higher estate taxes. Meanwhile, the church, which owned considerable property, didn’t pay taxes.

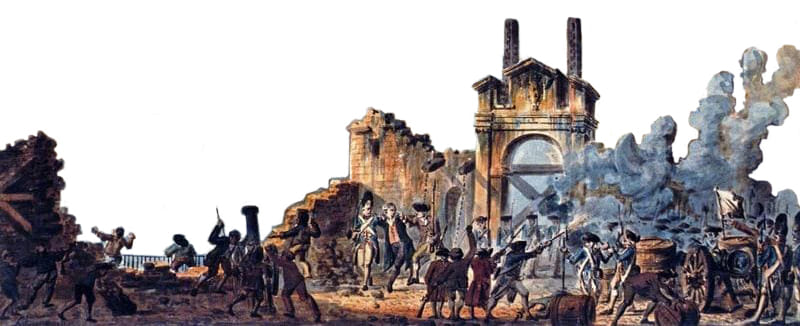

The Storming of the Bastille, Photo courtesy of Jean-Pierre Houël

The Storming of the Bastille, Photo courtesy of Jean-Pierre Houël

On the afternoon of July 14, a violent uprising took place in Paris. It climaxed with the storming of the medieval prison known as the Bastille. That evening, 15 miles away at the opulent Palace of Versailles, the monarch known for his extravagant lifestyle asked a duke if the attack on the fortress was a revolt.

“No, sire,” came the reply, “a revolution.”

But revolutionaries, like king and country, needed cash. Enter a monetary note known as the assignat.

Church lands for sale

King Louis had tried to appease his subjects by creating the National Assembly (left). It represented commoners in France’s General Assembly. But voting in that latter chamber belonged solely to property owners. Less than a month after the July 14th uprising in Paris, the National Assembly voted August 4 to abolish the feudal land-owning system.

King Louis had tried to appease his subjects by creating the National Assembly (left). It represented commoners in France’s General Assembly. But voting in that latter chamber belonged solely to property owners. Less than a month after the July 14th uprising in Paris, the National Assembly voted August 4 to abolish the feudal land-owning system.

Helping to pull those strings was lawyer Maximilien de Robespierre (right), a rising political star in the Revolution. The idealistic and persuasive leader was also behind the plan to make the king “Louis the Last,” along with anyone else judged to be an enemy of the Revolution. The fear and bloodshed during this chaotic period in France’s history came to be called the Reign of Terror.

Helping to pull those strings was lawyer Maximilien de Robespierre (right), a rising political star in the Revolution. The idealistic and persuasive leader was also behind the plan to make the king “Louis the Last,” along with anyone else judged to be an enemy of the Revolution. The fear and bloodshed during this chaotic period in France’s history came to be called the Reign of Terror.

The vengeful Robespierre supported the National Assembly’s seizure of all clergy-owned properties and selling them to finance the Revolution. Anyone could buy land by exchanging their copper sous, or sols, for a paper assignat. Notes could then be used to purchase former church land.

Assignat’s Designer

Robespierre tasked engraver-printer Nicolas-Marie Gatteaux (left) with creating the new Republic’s monetary note. Already known for designing tax stamps and lottery tickets, Gatteaux didn’t have long to wait for inspiration.

Robespierre tasked engraver-printer Nicolas-Marie Gatteaux (left) with creating the new Republic’s monetary note. Already known for designing tax stamps and lottery tickets, Gatteaux didn’t have long to wait for inspiration.

On August 25, the National Assembly introduced the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Taking its lead from the US Constitution ratified the year before in 1788, the French document proclaimed liberty, equality, the unalienable right to own property, the right to resist oppression, and one vote per man.

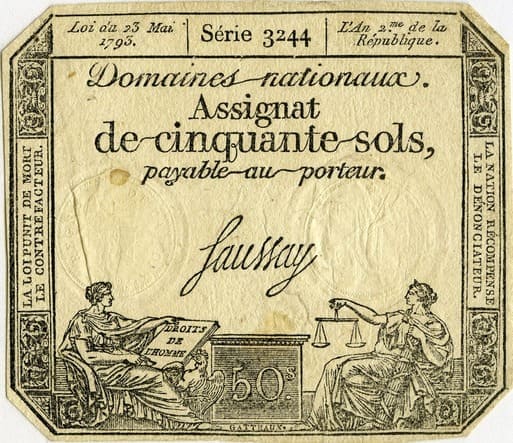

For the assignat, Gatteaux drew an allegorical setting that featured Justice holding the scales and France holding a tablet inscribed with “les droits de l’homme” which translates as “The Rights of Man.” For an added touch, he included the Revolution’s symbol, le Coq Gaulois or “The Gallic rooster”, (seen near lower left corner). Gaul, the ancient country that became France, and rooster share the Latin word gallus. This play on words evolved into a symbol of French independence in time of war. By December of 1789, assignats were rolling off the presses installed in a shuttered convent in the Place Vendôme.

For the assignat, Gatteaux drew an allegorical setting that featured Justice holding the scales and France holding a tablet inscribed with “les droits de l’homme” which translates as “The Rights of Man.” For an added touch, he included the Revolution’s symbol, le Coq Gaulois or “The Gallic rooster”, (seen near lower left corner). Gaul, the ancient country that became France, and rooster share the Latin word gallus. This play on words evolved into a symbol of French independence in time of war. By December of 1789, assignats were rolling off the presses installed in a shuttered convent in the Place Vendôme.

In the beginning, assignats made money for the Revolution. But as Robespierre upped his purge of enemies – some 17,000, including Louis XVI in 1793 – he also allowed for the overprinting of assignats. Hyperinflation became rampant. The note’s value plummeted. The Revolution lost forward momentum. Robespierre’s Reign of Terror was out of control. In its destructive wake, a counter-insurgency arose. In 1794, Robespierre followed in the footsteps of Louis the Last to the guillotine.

The end of the assignat

On a February morning in 1796, the presses, plates, and paper that had produced the Revolution’s assignats were taken from the old convent and placed in the center of the Place Vendôme. Before a large crowd of Parisians, the machines were broken and the paper burned.

On a February morning in 1796, the presses, plates, and paper that had produced the Revolution’s assignats were taken from the old convent and placed in the center of the Place Vendôme. Before a large crowd of Parisians, the machines were broken and the paper burned.

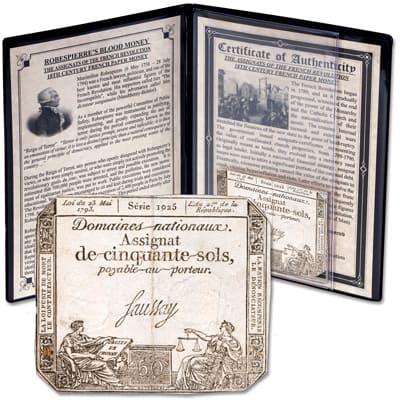

But a number of these historic notes survived, and Littleton Coin Company has several available from 1789 to 1796 for collectors. The date is our choice. Each affordable assignat comes with an illustrated story card and a certificate of authenticity in a handsome display folder. They are a unique addition to a world currency collection or a gift for a budding numismatic historian you may know.