Meet Pioneering Lawyer, Poet & Priest Pauli Murray

Before we get to the first 2024 U.S. Womens quarter, let’s take a quick look back at history.

The year is 1910. Women don’t have the right to vote. Native Americans aren’t considered U.S. citizens.* State and local governments continue to segregate African-Americans 14 years after a Supreme Court’s decision based on “separate but equal”. And political activist Emma Goldman is the first and only woman to speak publicly in favor of same-sex rights, a legal and social taboo.

On November 20, 1910, the fourth of six children born in Baltimore to nurse Agnes Fitzgerald and teacher William Murray is named Anna Pauline. A descendent of African-Americans slaves and slave-holding whites, the three-year-old toddler is raised by family in Durham, NC after Agnes dies.

The Road to Justice

Blessed with a quick mind, an unquenchable desire to read, and boundless energy, the teen is given free tuition to Hunter College in New York City. Despite the 1929 stock market crash and resulting Depression which makes jobs scarce, Pauli finally graduates in 1933 with a degree in English literature.

The change in first name comes from exploring an androgynous identity. According to the website of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice in Durham, “Murray actively used the phrase ‘he/she personality,’ during the early years of their life. Later in journals, essays, letters and autobiographical works, Pauli employed ‘she/her/hers’ pronouns.”

It’s also the professional start of pioneering achievements across a landscape of tumultuous 20th century changes. In 1936, Pauli helps found the nonpartisan Workers’ Defense League (WDL), which focuses on workers’ rights. It becomes a lifelong interest.

In March of 1940, Pauli is arrested in Richmond, VA and charged with disorderly conduct for refusing to sit on the broken seats at the back of a segregated bus traveling to North Carolina. The WDL sends Pauli back to Richmond six months later to raise money for the legal fees of an imprisoned sharecropper. His case opens the door to a lifelong friendship with fellow justice advocate and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

The fundraiser also presents Pauli with an opportunity to attend law school. In the audience are jurist Thurgood Marshall and Howard College School of Law professor Leon Ransom. The former writes a recommendation letter and the latter gets Pauli a scholarship. Pauli receives honors as the top student in the Class of 1944. She is the only woman. But because of gender, Harvard University turns down her application for post-graduate work.

The Post War Decades

Driven by a determination similar to that of African-American pilot Bessie Coleman, Pauli goes instead to the University of California-Berkeley’s Boalt School of Law. It leads to a masters’ thesis titled The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment. The degree is awarded in 1945.

That same year, the nation’s first anti-discrimination law is passed in the Alaska Territory, thanks to Elizabeth Peratrovich, a member of the Native American Tlingit Tribe. After passing the California bar, Pauli is named a deputy attorney general in California, the state’s first African-American to hold such an office.

A return to the East Coast brings a commission from the Women’s Division of Christian Service of the Methodist Church. It wants a compilation of legislation enforcing racial segregation. In 1951, it prints Pauli’s 776-page document titled States Laws on Race and Color. Three years later, Thurgood Marshall uses it successfully to argue before the Supreme Court the unconstitutionality of state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools as codified in the court’s 1896 “separate but equal” decision.

Like fellow poet, writer and activist Maya Angelou, Pauli spends 1960 teaching at the University of Ghana in Africa. With a return to America, President John F. Kennedy appoints Pauli to his Commission on the Status of Women. Its chair? Eleanor Roosevelt. Its charge? Examine questions of equality in education, work and under the law. Also in 1961, same-sex relationships slowly start to be decriminalized around the country. But Pauli never moves in with longtime partner, Irene Barlow, the office manager of a New York law firm where they had met.

Professor, Poet, Priest

In another pioneering achievement, Pauli is accepted into Yale University’s rigorous program for teaching law and becomes the first African-American to receive a doctor of jurisprudence degree in 1965 from the Ivy League school.

Pauli goes on to help found the National Organization of Women with feminist writer Betty Friedan. But Pauli leaves, dissatisfied it’s not addressing the issues of African-American and working-class women.

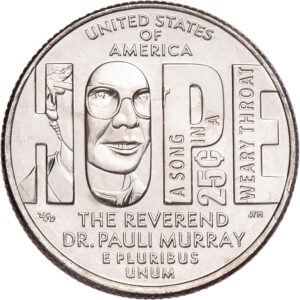

In 1970, Dark Testament and Other Poems comes out. It’s a compilation published in various periodicals between 1933 and 1941. The reverse of the 11th U.S. Womens quarter shows Pauli’s eyeglass-framed face in the “O” of the word hope, a key word in Verse 8 of Dark Testament. It emphasizes reforms are possible when rooted in optimism. In the “P” and “E” of hope, illustrator Emily Damstra of the U.S. Mint’s Artistic Infusion Program includes a phrase from the poem: hope is a song in a weary throat.

By 1972 when she is 62, Dr. Murray is a tenured professor at Brandeis College in Waltham, MA, where she helps pioneer the American Studies department. But she resigns her post to enter the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York that fall. The next year, Irene Barlow dies in Manhattan at the age of 59.

Three years later, the Episcopal Church’s General Convention votes to change its policy on the ordination of women priests, effective January 1, 1977. Seven days later that January, Rev. Murray becomes the first African-American woman vested as an Episcopal priest in a ceremony at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. When Pauli dies in 1985, she is laid to rest next to Irene in a Brooklyn cemetery.

*Later in 2024, the U.S. Mint is scheduled to release a U.S. Womens quarter honoring Zitkala-Ša, the Yankton Dakota Sioux tribal member who was instrumental in lobbying for passage of the federal Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. The mint is also striking a centennial tribute to passage of the law itself on the one-year-reverse of the 2024 Native American dollar.

SOURCES:

Keaveney, Hiroki Kimiko. “Christian, Queer and Interracial: The Story of Pauli Murray and Irene Barlow.” September 2016. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/xg94hr05w

Mintz, S., & McNeil, S. (2018). “Emma Goldman, Anarchism: What It Really Stands For.” Digital History. Accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=1339

“Life Story: Pauli Murray (1910-1985).” Accessed November 17, 2023. https://wams.nyhistory.org/confidence-and-crises/world-war-ii/pauli-murray/

Olivares, Samy Nemir. “How Civil Rights Pioneer Pauli Murray’s Legacy Lives on Today.” Teen Vogue, February 7, 2023. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/how-civil-rights-pioneer-pauli-murrays-legacy-lives-on-today

Rothberg, Emma. “Pauli Murray.” Accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/pauli-murray

Ryzik, Melena. “Pauli Murray Should be a Household Name. A New Film Shows Why.” The New York Times, September 15, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/15/movies/pauli-murray-documentary.html

Schulz, Kathryn. “Saint Pauli.” The New Yorker, April 17, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/17/the-many-lives-of-pauli-murray

“The Pioneering Pauli Murray: Lawyer, Activist, Scholar and Priest.” Accessed October 30, 2023. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/pioneering-pauli-murray-lawyer-activist-scholar-and-priest

“Who is the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray?” Accessed September 6, 2023. Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice

What a lovely, informed tribute to a fascinating person.

Thanks for your kind words & for visiting!