5 Who Danced Their Way to Global Fame

If ever there were a coin design with a richly complex story told in such a meaningful way, the 2023 Native American dollar reverse might be it!

Struck just for 10 weeks, the legal tender coin celebrates the ‘Five Moons’ – Native American classical dancers all from Oklahoma who achieved international recognition. The number originated with performances at the 1967 Oklahoma Indian Ballerina Festival which celebrated the 60th anniversary of the Sooner State joining the Union in 1907.

With music by Cherokee-Quapaw composer Louis Ballard Sr., a ballet titled “The Four Moons” featured separately choreographed solos in which each dancer paid tribute to her respective tribal heritage. As sisters Maria and Marjorie Tallchief were of the Osage Nation, the original number was four. But counting them individually results in the number five.

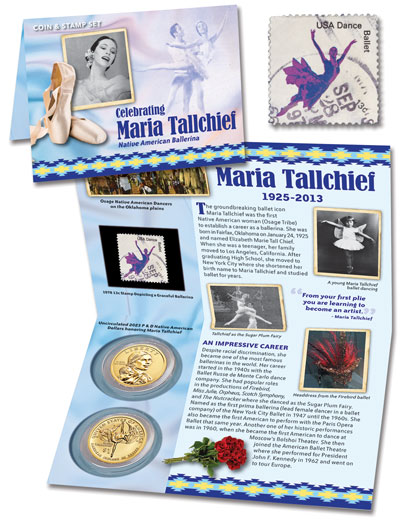

Look for an upcoming Heads & Tails blog post to coincide with the U.S. Mint’s 2023 U.S. Women Quarter release honoring just Maria Tallchief. But on this 2023 Native American dollar, Maria, the older of the two sisters, appears at the design’s center – in a position in ballet known as an attitude penchée for the inclined balance achieved on pointe.

Let’s meet the four other Moons and discover their unique contributions.

But first, ballet’s back story

Since before the Civil War, touring European dance troupes brought ballet to American audiences. Now, as then, it’s an athletic art form largely attributed to Russia, even though France and Italy can rightly lay claim to its origins during the Renaissance.

With a theatrical tradition rooted in folk stories, Russia also gave the ballet world a library of classic narratives. The third influence from Russia was the classical ideal: tall dancers with long limbs and elegant, swan-like necks, plus dark hair and features that contrasted well under harsh stage lights. The Five Moons had a lot in their favor as they joined the Ballets Russes.*

Alex J. Tall Chief (original spelling) was a full-blooded Osage who ran the movie theater in Fairfax, OK, when his wife, Ruth, noticed their daughters had a natural aptitude for dance and music. She enrolled them in local lessons. When they showed exceptional promise, the family moved to Los Angeles. There, Marjorie and Maria trained with, among others, Bronislava Nijinska, a noted Polish-born dancer who had performed with the Ballets Russes. In 1939, she relocated to southern California as political tensions rose in Europe ahead of World War II.

Before too long, Marjorie left L.A. for New York. After a brief stint with the newly formed American Ballet Theatre, she switched corps, signing on with the Ballets Russes. She never looked back. She was to have said, “Great opportunity will present itself to every person at some point in time, but you have to be ready for that opportunity.”

Starting in 1957, Marjorie danced with the Paris Opera Ballet, becoming the first American to be made a première danseuse étoile, or principal dancer. Marjorie’s most famous roles included those in Annabel Lee (1951), Romeo and Juliet (1955), Camille (1958), Pastorale (1961), and Ariadne (1965).

In 1958, Marjorie became the first American ballerina since WWII to perform in Moscow’s famed Bolshoi Theatre. One critic described her as “a brilliant, dynamic dancer with a svelte and flexible body,” adding, “Through her quasi-acrobatic virtuosity, she embodies the perfect dancer for our time.”

Oklahoma Indian Ballerina Festival

In 1967, Marjorie choreographed and danced her own solo for composer Louis Ballard’s “Four Moons” to honor her Osage heritage. In 1980, she helped her sister found the Chicago City Ballet. When she died at 95 in 2021, Marjorie was the last of the Five Moons still living.

Also choreographing and performing their own 1967 solos were Moscelyne Larkin and Rosella Hightower, two of the youngest ballet dancers to leave their native state for the Ballets Russes, which often auditioned performers in New York.

Moscelyne’s father, Reuben Larkin, was a miner who descended from the Eastern Shawnee-Peoria Tribe. He married Eva Matlagova, a Russian-born folk dancer whom he had met when she was touring through Oklahoma. When the couple divorced, Eva opened a dance school in Tulsa. At 13, Moscelyne moved to New York for further training. Mikhail Mordkin, who had danced with the Ballets Russes, stopped a class one day to say to the teenager, “You’re a little fish now, but one day you’re going to grow up and be a big fish and you’re going to eat up all the other fish.”

At 15, Moscelyne signed with the Ballets Russes and embarked on world tours with favored roles in Les Sylphides, Paganini, Graduation Ball and Aurora’s Wedding. Marrying fellow corps member Roman Jasinski, and having a son, brought the arc of her career back to Tulsa.

The couple took the reins of her mother’s established dance school. Then they took ballet to the next level by launching what would become the internationally acclaimed Tulsa Ballet. Of equal cultural importance, Moscelyne founded the Oklahoma Indian Ballerina Festival in 1957, to coincide with the 50th anniversary observance of the state’s admission to the Union.

From Oklahoma to the French Riviera

Rosella Hightower’s father was of Choctaw descent; her mother, Irish. After a move from Durwood, OK to Kansas City, MO due to her father’s railroad job, Rosella became a Charleston and tap dance champion at the age of 7 and a star baseball player. Rosella began studying classical dance when she was 11. At 13, she was in the audience when a Russian ballet troupe performed and “decided then that that was what I was going to do with my life.” A year later, she was training in New York “and I felt in my place on stage.” At 18, she won her audition with the American Ballet Theatre.

But traveling to France brought her to the attention of the Ballets Russes. She signed on, and excelled in lead roles choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska for Petrouchka and Sleeping Beauty. Known for her strong work ethic, Rosella also earned critical acclaim for the title role in Giselle, for which she had only five hours to prepare, and then three days later, for the lead in Swan Lake. When, in 1961, she retired from performing to the French Riviera, she established a training school known today as École supérieure de Danse de Cannes Rosella Hightower. She also returned to Oklahoma in 1967 to perform her own solo choreography in which she honored her Choctaw roots.

Youngest Native American Ballerina to Go Pro

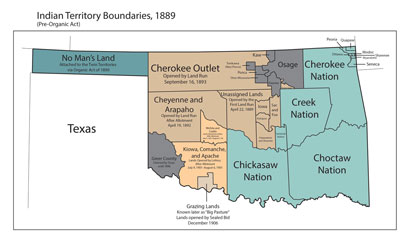

Under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole nations – known as the Five Tribes – and later other Indigenous tribes that included the Osage and Lenape were forced from their ancestral homelands by the federal government and relocated to the Oklahoma Indian Territory.

Born in 1929, Yvonne Chouteau was of Shawnee descent, thanks to her father, Corbett, whose three prior generations of Chouteau men had married Shawnee women from the western Mississippi River Valley. Growing up in Oklahoma City where Corbett worked for an oil company and her mother, Lucy, was a schoolteacher, Yvonne saw Alexandra Danilova dance with the touring Ballets Russes. Before too long, she was studying with her at the School of American Ballet in New York.

At 14, Yvonne joined the Ballets Russes as the youngest dancer ever to do so. At 25, she had her first solo role in the comic ballet Coppelia. During her 14 years with the company, she soloed in Gaite Parisienne, The Nutcracker, Les Sylphides, Pas de Quatre and Romeo and Juliet, and was hailed as a dancer of great radiance and lyricism. Yvonne married Miguel Terekhov, a dancer in the Ballets Russes’ corps. In 1960, they moved to Oklahoma City with their two children and established the forerunner of today’s Oklahoma City Ballet.

More importantly, the couple established the first fully accredited dance department in the United States at the University of Oklahoma at Norman that is still going strong. In 1967, Yvonne performed her own choreography to honor her Shawnee tribal heritage at fellow dancer Moscelyne’s second American Indian Ballet Festival designed to coincide with Oklahoma’s 60th anniversary of statehood.

Last Curtain Call for the 5 Moons

Nearly 25 years later, the Five Moons gathered in 1991 for the dedication of Flight of Spirit. The commissioned mural in the statehouse rotunda features the five ballet dancers symbolically paired with five Native American dancers by Chickasaw artist Michael Larsen.

While that event was the Five Moons last public reunion, it’s clear theirs is a legacy that lives on. Just like the phases of the moon, also engraved on the 2023 Native American reverse, the creative cycle renews itself.

*Balletomanes who also are coin collectors know there were three different Ballet Russe. In their last years, they were collectively referred to as Ballets Russes, with many of the dancers performing interchangeably with the two remaining corps.

SOURCES:

Laubacher, Kyra. “Iconic Five Moons Ballerinas to Be Featured on the U.S. $1 Coin.” Pointe Magazine, November 22, 2022. https://pointemagazine.com/five-moons-ballerinas-dollar-coin/

Meier, Allison. “How Five American Indian Dancers Transformed Ballet in the 20th Century.” Hyperallergic, January 28, 2016. 2023. https://hyperallergic.com/271205/how-five-american-indian-dancers-transformed-ballet-in-the-20th-century/

Zemel, Jane. “Esprit de corps.” Tulsa People, February 21, 2012; updated January 10, 2020. Accessed April 3, 2023, https://www.tulsapeople.com/blogs/esprit-de-corps/article_0b48fabe-806f-598d-be1e-b96c4da7d65b.html

“American Indian Ballerinas” abstract review. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, January 1, 1998(Volume 22, Issue). https://meridian.allenpress.com/aicrj/article-abstract/22/3/223/210805/Reviews?redirectedFrom=PDF

“Rosella Hightower (1920-2008)” Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.operadeparis.fr/en/magazine/350-years/tessitura/rosella-hightower-1920-2008